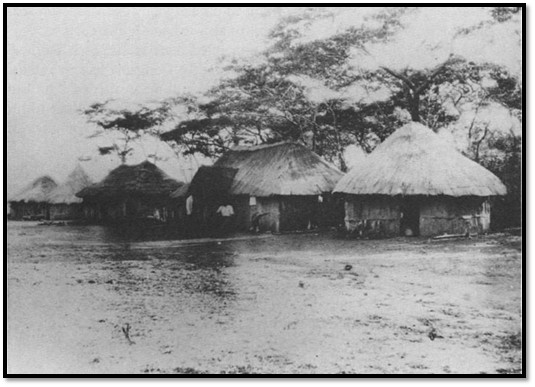

The British South Africa Company – establishing an administration in the early days of the occupation of Mashonaland

Introduction

The core of this article is a paper by Honest Elias Koke entitled Unfulfilled Promises and Desires: The British South Africa Company (BSAC), Settler Politics and the Development of Southern Rhodesia's Fiscal System, 1890–1922 which although it is about the introduction of the taxation system in Southern Rhodesia through the British South Africa Company {BSAC} contains much useful information about how the administration developed to cope with the changes. This has been supplemented with additional details seen in the references at the end of this article and footnotes.

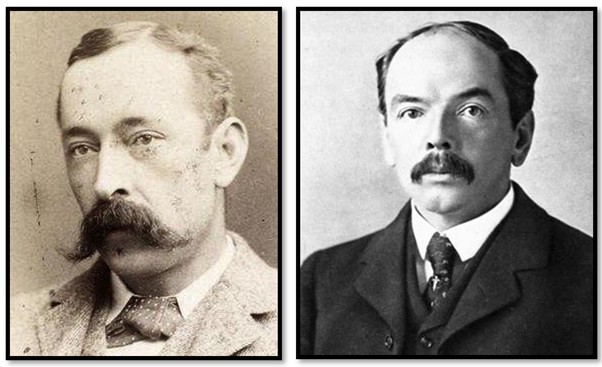

From the start the administration provided by the BSAC was totally inadequate for the task. The first administrator, A.R. Colquhoun, resigned in August 1891 frustrated by the lack of administration and the lack of support from Rhodes.[1] Dr L.S. Jameson took over as administrator. However he was ill equipped by experience or temperament to install an administration and given an impossible task. “In 1893 Jameson’s staff consisted of less than twenty administrative in a territory of approximately 285,000 square kilometres.” [2]

Resident magistrates were appointed with the existing Roman-Dutch law of the Cape Colony applied to Mashonaland but as Gann writes, “But none of the early Resident Magistrates possessed much legal experience beyond the sort they had acquired in the orderly room,”[3]

Overview

This paper examines how the British South Africa Company (BSAC) a Royal Charter company,[4] found itself in September 1890 in charge of the administration of Mashonaland; present-day Mashonaland Central alone comprising 28,347 square kilometers. In 1893 after the invasion of Matabeleland[5] that area under the charter company’s administration increased to the area of present-day Zimbabwe; 399,757 square kilometers.[6]

The Royal Charter, granted on 20 December 1889 initially for 25 years, but extended by a further 10 years expiring in 1924, gave the BSAC the authority to occupy[7] and administer the territories that would later become Southern and Northern Rhodesia, present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia, and was in line with the British imperial policy in the nineteenth century of, “imperialism on the cheap.”[8] It was a strategy designed to lessen the burden on the British taxpayer by using chartered companies to act as agents of imperial expansion. The BSAC maintained it had sufficient financial backing through its own capital, that of its associates, such as De Beers Consolidated Mines and the personal wealth of Cecil Rhodes to finance the administration of these territories.

Lord Salisbury[9] believed that Rhodes’ plan through the BSAC was the best. “They would accept the expense and take the risks and the imperial government need not be directly involved beyond providing its blessing to the company and recognition of its sphere of operations.”[10]

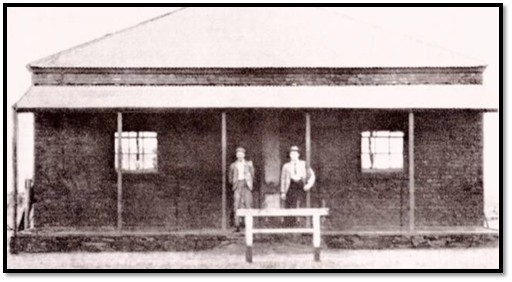

NAZ: The Administration had its first offices in pole and dhaka huts, and they served from the Occupation in 1890 until the middle of 1892.[11] This building which pre-dated "The Stables" served as the first office of the Administrator of the country, in the first brick building.

Lord Knutsford[12] wrote to Queen Victoria’s secretary, “I am confident that a strongly constituted company will give us the best chance of peaceably opening up and developing the resources of the country south of the Zambezi and will be most beneficial to the native chiefs and people. Such a company has been formed and all the capital subscribed without going to the public.”[13]

Sir Henry Loch, High Commissioner for Southern Africa, “…fully as much as Rhodes, believed that it was the destiny of the British people to occupy the high plateau north of the Limpopo.”[14]

Once the flag had been raised at Salisbury (present-day Harare) on 13 September 1890 and the men of the Pioneer Column disbanded on 1 October 1890[15] the main issue became how the newly-acquired territory was to be administered and the cost of financing its organisation. In fact on examination, it turns out to have been initially extremely ad hoc.

The BSAC never contemplated using the company’s capital for mining operations

Rhodes believed the men of the disbanded pioneer column would create syndicates that would enlist new sources of capital once they had registered their gold claims and the risks would be carried by investors.

Gold fever did run high. As one early settler observed, “such was the faith in the gold country that the officials thought that soon we would have several reefs eclipsing the Johannesburg main reef, and that next season the country would be swarming with a population and we – equally sanguine – were scouring the country in search of these reefs.”[16]

The mining regulations allowed anyone to get a licence to prospect for a small fee but they needed to show they had worked their claim within four months and get an inspection certificate. If the claim was payable, the prospector was required to organise a company in which the BSAC had a 50% shareholding. However many claim holders then sold their claims to companies which were then floated on the London Stock Exchange. Most descriptions of Mashonaland gold prospects ranged from optimism to downright deceit which soon brought disillusion to overseas investors.

Funding the expected costs of administration

Clearly in order to administer its newly acquired territories, some form of revenue was required. The BSAC hoped to obtain the bulk of its revenue from the sale of its share of the 50% shareholdings that were demanded from newly established mining companies. But without plant to crush the hard quartz material that contained the gold, production was limited and gold output very low and this source provided little revenue. In 1893 only two mining companies were floated on the London Stock Exchange for which the BSAC received £116,270.[17]

By 1893 the accounts were showing a loss and the secretary of state in London wrote to the Rhodesian administrator expressing his displeasure with the chartered company stating that “The board [of directors] cannot understand without explanation how the Company’s [financial] affairs could have been allowed to drift into their present conditions.” In fact, the only reason the chartered company was solvent was through a monthly subsidy from the De Beers.

Custom and excise duties were introduced and levied at Fort Tuli and Old Umtali, but the amounts were small in comparison to expenses. Possibilities of taxing the early settlers was very limited. Richard Hodder-Williams described them as, “mere storekeepers and small-time prospectors”[18] who lacked the ability to develop their land for commercial agriculture, or any other business except small trading stores and inns.

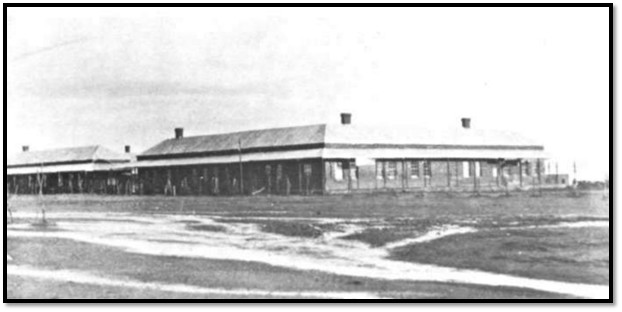

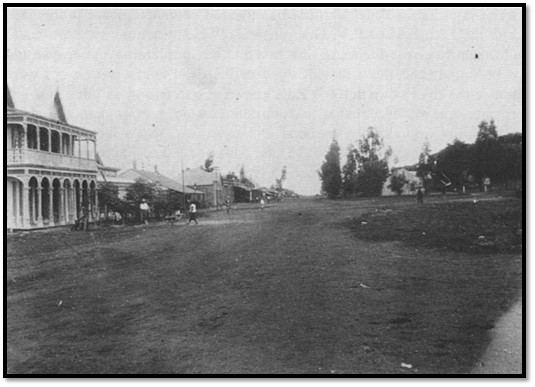

NAZ: Fig. 2 The Stables", in 1898 when the building served as the Mining Commissioner’s Office. The building to the left was the Surbey Office[19]

Reducing administration expenditure

Sir Henry Loch had insisted on the initial force of 500 BSAC Police; his justification was the threat of a Boer trek into Mashonaland,[20] but his real reason was to exercise control on Rhodes.

“Rhodes had spent £700,000 in less than a year; yet, the board complained, there was no evidence that he was heeding their injunction to cut back expenditure.”[21]

Rhodes ordered cuts, but the only possible saving that could be made was to drastically reduce the numbers of BSAC Police. Marshall Hole in Old Rhodesian days writes, “The company’s funds were running low, and hardly any revenue was to be expected for months to come. The most ruinous item of expenditure was the cost, amounting to about £150,000 a year, for the police force, which the Imperial authorities required the company to maintain as a safeguard against attacks from the natives and Rhodes and Jameson put their heads together to devise some means of ridding themselves of this white elephant. They pooh-poohed the notion that the settlers, who were mostly men in the prime of their vigour, accustomed to firearms and thoroughly used to taking care of themselves, required a permanent body of 600 police to protect them from the invertebrate native tribes of Mashonaland…”

The police force was reduced from 650 to 150 of all ranks and Jameson promised Rhodes to do so by the end of 1891. Many left the country, those that remained were granted police farms of 1,500 morgen (3,175 acres)[22] A volunteer force of 500 were recruited into the Rhodesia Horse as a standby force at Salisbury and Victoria, following the example of the Boer commandos, to provide security from the amaNdebele.

Tensions between settlers and the BSAC arise

Settler grievances were evident even in 1902, the year Rhodes died. When Beit and Jameson visited they were soon inundated with complaints. “The most serious were the extent of mining royalties payable to the BSAC, the high cost of living, the expense of sending goods by rail and the question of whether the company owned the land in its commercial or merely in an administrative capacity.”[23]

Some small concessions were made; the mining levy was cut, smallworkers received better terms and railway rates were reduced.

The chartered company’s administration expenses created tensions between the company itself, its shareholders and the settlers.

Clearly the view of the settlers was that the BSAC should maximise its expenditure on infrastructure, such as schools, hospitals and a transport network that would enable the prosperity of the country to draw in even more settlers.

In addition however, those tensions arose over the charted company’s own administrative expenses (its commercial account) and those expenses involved in administering Mashonaland from 1890 and Matabeleland from 1893 (the administration account) In order to see that expenses were properly apportioned the settlers wanted access to the chartered company’s own audited balance sheet and income and expenditure accounts.

The settlers, especially farmers and miners, believed the BSAC was subsidizing its own commercial account from the administration account at their expense. Their argument was based on the principle that as the BSAC owned all of the country’s land and mineral rights, it should finance the administration of the country.

Shareholders obviously hoped for distribution of maximum profits in the form of dividends and believed development of the country was a secondary issue.

The disputes between settlers, shareholders and the BSAC over how to manage and administer the country’s finances resulted in a different tax system to other British colonies. Although farmers and miners had different viewpoints, at times they united to oppose new tax measures, for example, the Land Tax in 1914 and the Income Tax in 1918.

The formation of the Legislature Council in 1898 led to an order from that body that the BSAC must separate its commercial account from the administrative account and follow “strict” financial accounting procedures created much animosity between the Company and the shareholders on one side, and the Company against farmers and miners on the other.

However the Legislature Council was initially made up of four elected members and thirteen appointed members and the elected members votes on the chartered companies revenue and expenses were considered merely an expression of their opinion as they could always be outvoted by the appointed members or just ignored by the BSAC’s officials.

In 1903 Milton[24] requested that the elected members on the Legislative Council be raised to seven with seven appointed members and the administrator be left with a casting vote and this was reluctantly agreed by the colonial office.

Sir Ernest Guest,[25] said the Company, “dictated what the [settlers] were to have for breakfast,” meaning it had the power to listen or not. The BSAC directors felt the same and that elected members could not push through budgets beyond the BSAC’s means or shareholders expectations.

This infuriated the settlers on the Legislature Council so much that they began to demand the BSAC publish its revenue and expenditure accounts.

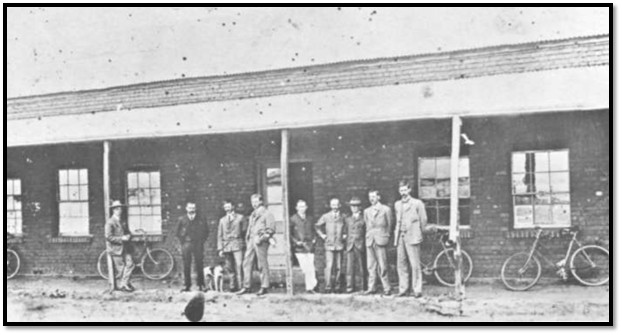

NAZ: [26] The Mining Commissioner’s staff in 1907

The BSAC’s division between commercial and administrative revenue and expenses

Koke in his article delves deeply into this issue, the split between the commercial and administrative accounts, that caused continual disagreement between the BSAC’s administration and the settlers. The commercial account constituted all the income the Company received from its commercial investments in the country. The administrative account was made up from royalties, fees and taxes collected by the company and both accounts should have their appropriate expenses.

From 1893 to 1913 the BSAC maintained that its administrative account operated on a budget deficit. The settlers, chiefly the farmers, said the company apportioned expenses that should be on its own commercial account onto the administration account.

The BSAC’s attempts to raise fresh capital

The combination of budget deficits and a requirement for fresh capital to finance new commercial projects led the directors in 1903-6 to conclude they needed to raise the share capital of the company by another £1 million. In a lengthy 1903 operations report they reported good progress in the country with an expansion in the mining and farming sectors and proposed issuing new shares to the value of £300,000.

The shareholders however were not convinced. They knew about the conflict with settlers, that the company was still running a budget deficit and could not afford to pay dividends. The market price of the BSAC’s shares dropped once the new shares were issued.

This failure prompted company officials to look at local sources for fresh revenue and the company treasurer, Francis Newton, proposed increasing African taxation from one pound to two pounds per annum saying, “the native portion of the population should in good times be made to bear their fair share of the burden of administration of the country.” However the Colonial Office rejected Newton’s proposal saying Africans were already paying more than they could afford, earning an average salary of fifty shillings per month.

The controversy continued over past administrative deficits and land and mineral rights. In 1907 a committee visited the country and made more concessions. The BSAC agreed to promote land settlement, introduce reforms in the civil service, revise mining royalties and issue simpler land titles. Most significantly, appointed members to the legislative Council were reduced to five, giving elected members a majority.

However the Legislative Council was still unable to raise taxes or change the BSAC’s land or mineral rights without the Administrator’s consent, a condition that nullifies the elected members majority.[27]

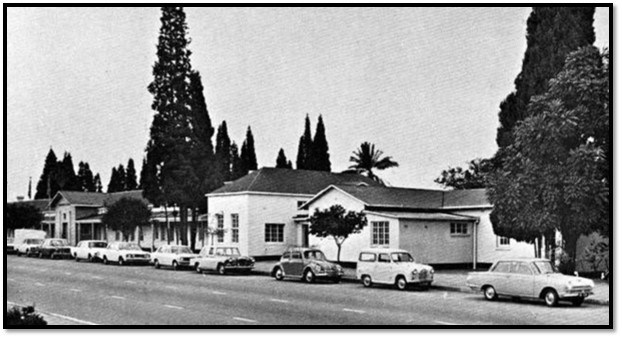

NAZ: ‘The Stables’ in 1974 will be familiar to many readers

The outbreak of World War I and the introduction of Income Tax for the first time

In 1914, with the Royal Charter about to expire, frustrated settlers formed the Rhodesia League Party to force the BSAC to negotiate. The settlers wanted complete control over the country’s budgets and revenue collection, that the Imperial government take control of the administration and hold a referendum on whether the country should join the Union. Charles Coghlan, the future prime minister, argued that with the outbreak of war the settlers were not financially ready to take over the administration of the country and almost all the League’s candidates were defeated in the elections. The British government agreed and the charter was extended in the following year to 1923.[28]

War costs necessitated the introduction of income tax on Europeans. However this was resented by the settlers who said that part of what they paid would land up in the pockets of BSAC shareholders and would not benefit the country.

A new organisation was formed, the Responsible Government Association (RGA) backed up by many of the country’s farmers, miners, civil servants, and others whose argument was that only a self-Responsible Government should be allowed to tax the country’s citizens as the tax revenues would be for the sole benefit of the country and not for the part benefit of the BSAC’s shareholders. Koke writes that the evidence from recent research by Kudakwashe Chitoro[29] confirms that the BSAC directors and Rhodes were driven more by imperial influences than by commercial ones and that they frequently denied shareholders claims. This despite the fact that the BSAC was listed on the London Stock Exchange and the value of its shares determined by shareholders perceptions of its future value.

The land question came up again in 1914 with the elected members of the Legislative Council asking for an immediate settlement of the land question and declaring the BSAC did not own the unalienated land in its private capacity.[30]

NAZ: Pioneer Street in 1891

NAZ: Pioneer Street about 1900

The BSAC is always in a Catch-22 situation

From a shareholders view the company’s aim was to make a financial success and earn them profits, but from the settlers view they demanded that it should work toward developing the country. The settlers, as the taxpayers, wanted control of the country’s Legislative Council and the tax system to approve the levels of revenue collection and ensure the expenditure was for the benefit of the country.

This made a difficult course to navigate for the directors.

Unlike the other African charter companies, the Royal Niger Company and Imperial British East African Company, the BSAC received no financial assistance from the Colonial Office.

The role of the indigenous Africans

African people paid taxes from the earliest years being first introduced in Mashonaland in 1894 at a rate of ten shillings per hut having been authorised by the Colonial Office and then rolled out into the north-east of Rhodesia in 1901 and then into the north-western between 1904 – 13.[31] However, they played no part in the administration of the country that was solely European.

In addition, there was a strong feeling amongst all settlers and even missionaries and the Colonial Office that Africans should be brought out of their traditional barter economy and into the cash economy as quickly as possible. As Koke reminds us, Africans contributed immensely toward the country’s development through paying taxes and providing cheap labour but never received political representation in the administrative structure of the colony during the BSAC’s period of tenure until 1923.

Rhodes was one of the first in 1892–3 to propose taxing Africans in the form of a hut tax, but the concept was not supported by Jameson who felt Mashonaland lacked sufficient Europeans to collect the tax.[32] Opposition also came from the Colonial Office. However despite this, a hut tax was introduced by the BSAC and was approved in the 1894 Order in Council[33] eventually contributing to the outbreak of the 1896 / 97 Rebellion uprisings (Umvukela / First Chimurenga)

In 1903-4 of the total revenue of £435,000 nearly £130,000 was raised from Africans through taxes and customs.

Koke makes the point that the only exception to African political participation was in 1923 when the Rhodesia Bantu Voters Association was formed in the hope they would back the Responsible Government Association (RGA)

Africans prior to the occupation

Prior to 1890 the economy was barter based and from Mashonaland and other regions tribute was sent to the amaNdebele Kings, initially Mzilikazi and then Lobengula, in the form of grain, cattle, ivory and gold annually as tribute.

This came to a partial halt after the occupation of Mashonaland and a full halt after the invasion of Matabeleland and the death of Lobengula.

A.R. Colquhoun – first Administrator Dr L.S. Jameson – second Administrator

Administration was a heavy drain on the BSAC’s resources

In order to fund its occupation of Mashonaland the BSAC listed on the London Stock Exchange with an initial capitalization of one million £1 shares, and unlike the other African chartered companies that were subsidised by the Colonial Office, had to raise all the finance for the administration of the country

The Pioneer Column organised by Frank Johnson[34] was the first major expense costing £87,500 for the procurement of wagons and oxen, horses, uniforms, artillery and supplies.[35] The planned force of 190 pioneers[36] were not paid wages but promised 15 mining claims and a farm of 1,500 morgen (about 3,000 acres)[37] but Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa insisted on a police force accompanying the column, and these men were paid wages costing £200,000 per annum. Installing the telegraph line to Salisbury cost another £50,000.

The running costs of the administration was another burden after the flag was raised in Salisbury although the actual number of staff was always small. However, additional costs included:

- magistrates appointed to settle disputes and crime

- mining commissioners appointed

- licenses had to be issued for mining claims

- regulations needed issuing

- roads capable of ox-wagon traffic needed construction to different parts of the country

- a postal and telegraph system needed to be established

- townships laid out and municipal regulations devised

The administration burden was exceptionally heavy on the small white staff of the BSAC both as administrators and as a commercial business. In order to strengthen its administrative structure the BSAC added new departments in 1897-8 including Commissioner of Mines and Public Works in 1897, Department of Education in 1898, Native Department in 1898, and the Southern Rhodesia Legislative Council in 1898, which became the Treasury in 1903.

Administrative posts of the BSAC in the early days until 1923[38]

Chief Magistrates of Southern Rhodesia

24 July 1891 – 18 September 1891: A.R. Colquhoun(acting)

18 September 1891 – 7 October 1893: Dr Leander Starr Jameson, KCMG, CB

7 October 1893 – 10 September 1894: A. H. F. Duncan (acting)

Administrators of Southern Rhodesia

1 October 1890 – 10 September 1894: A. R. Colquhoun

10 September 1894 – 2 April 1896: Dr Leander Starr jameson KCMG, CB

2 April 1896 – 5 December 1898: The 4th Earl Grey

5 December 1898 – 20 December 1901: William Henry Milton (Administrator of Mashonaland and Senior Administrator of Southern Rhodesia)

5 December 1898 – March 1901: Hon. Arthur Lawley (Administrator of Matabeleland)

20 December 1901 – 1 November 1914: Sir William Henry Newton KCMG, KCVO

1 November 1914 – 1 September 1923: Sir Francis Chaplin

Acting Administrators of Southern Rhodesia

1894 – 1895: Colonel Francis Rhodes

1895 – 1897: Mr Justice Joseph Vincent

1897 – 1898: William Henry Milton

1898 – 1899: Hon. Sir Thomas Charles Scanlen

1899 – 1902: Hon. Arthur Lawley (Mashonaland)

1902 – 1903: John Gilbert Kotze

1903 – 1903: Hon. Sir Thomas Charles Scanlen

1903 – 1904: John Gilbert Kotze

1904 – 1909: Hon. Sir Thomas Charles Scanlen

1909 – 1914: Francis James Newton

1914 – 1923: Sir Clarkson Henry Tredgold, Sir Ernest William Sanders Montagu, and P. D. L. Fynn at various times.

Resident Commissioner

Following the Jameson Raid of 28 December 1895 a Resident Commissioner was appointed by the Colonial Office to oversee the BSAC. He reported to the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, who then reported to the Colonial Office.

5 December 1898 – 1 April 1905: Sir Marshall James Clarke

1 April 1905 – 1 April 1908: Richard Chester-Master

1 April 1908 – 1 April 1911: James George Fair

1 April 1911 – 1 April 1915: Robert Burns-Begg

1 April 1915 – 1 April 1918: Herbert James Stanley

1 April 1918 – 1 October 1923: Crawford Douglas-Jones

A Legislative Council was created in 1898 in Southern Rhodesia to advise the BSAC Administrator and the High Commissioner for South Africa in legal matters

Tensions between settlers and the BSAC over administration remains a constant until 1923

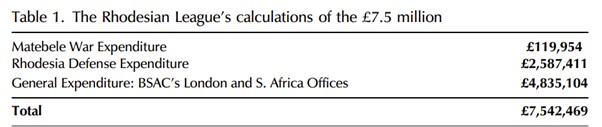

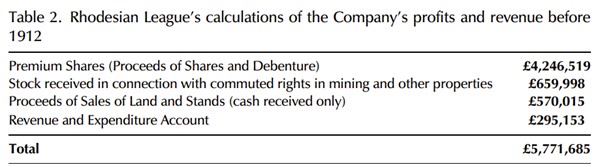

There were serious debates over the accuracy of the BSAC’s statements after the chartered company indicated in 1907 it had spent over £7 million developing the country.[39] An analysis by the Rhodesian League provided financial evidence this was overstated.

Note: compiled by H.E. Koke using statistics obtained from the Rhodesian League Election Pamphlet, March 1912.

The Rhodesia League argued on behalf of the settlers that these sums were not administrative expenditure and said the £5,771,685 profit declared by the BSAC should be deducted from the above (£7,542,469 - £5,771,685 = £1,770,784) and even that would be wiped out if the BSAC faced a valuation on some of its assets. For example, there were unrealised profits connected with commuted rights in mining and £424,464 worth of shares in the Rhodesia Railways Trust.

Note: compiled by H.E. Koke using statistics obtained from the Rhodesian League Election Pamphlet, March 1912.

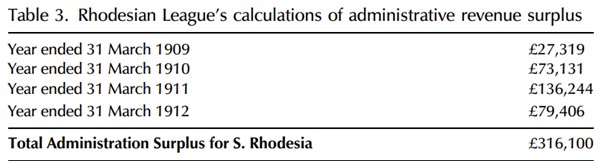

From the BSAC’s 1912 income and expenditure accounts the Rhodesian League claimed that in the period 1909-12 the company received administrative surpluses as shown below.

Note: compiled by H.E. Koke using statistics obtained from the Rhodesian League Election Pamphlet, August 1913.

A local well-known accountant, C. Raymer, after examining the BSAC’s accounts confirmed the company was making more profit than it declared.[40]

The settlers argued that the BSAC’s past administration losses should not be carried forward against any future self-governing country. The BSAC on its part did not like to raise funds without an understanding of how this would be repaid in the future. Sir George Goldie produced a report that proved completely unacceptable to the settlers. The BSAC directors produced a proposal that if the settlers admitted the debt (estimated at £7.67 million – much being railway development costs) they would sell a portion of their land and mineral rights at a future fixed cost.[41] This was again turned down and negotiations stalled.

Questions are asked if the BSAC should continue as Southern Rhodesia’s administrator

Arising from the above, in the 1914 elections the Responsible Government Association supported the continuation of the charter; the Rhodesia Unionist Association was opposed to this and favoured joining the Union of South Africa. Those opposed formed the Common platform their manifesto stating, “the longer the Chartered Company is allowed to retain the country’s administrative functions, the more securely will they be entrenched, and the higher will be the price which the people will eventually have to pay for their emancipation.”

Charles Coghlan[42] argued against the Common Platform’s position. He believed that the country was not ready for self-rule, especially after the BSAC’s 1913 accounts showed a deficit of £100,214. He believed the country was not yet strong enough to absorb the administration costs.

The BSAC labelled those supporting the Common Platform as agents of the Union of South Africa and in response stated:

- A new fiscal policy would accelerate development in Southern Rhodesia

- It would revise the Land Settlement Scheme and pay for its administrative costs

- They agreed to absorb accumulated deficits before 1914

- They agreed to separate their commercial and administrative accounts

In response, Common Platform supporters argued the company should have paid for acquiring and developing the country’s land and mineral assets and that the company’s deficits after 1914 incurred as a result of revenue shortfalls and the cost of public works could be shared.

They believed that they should make the decisions on important administrative matters and that the BSAC contribute toward government finance. This became a key criticism of the charter company rule during World War I. However the majority supported continued rule by the charter company and with WWI political activity was deferred until 1917.[43]

In 1915 the BSAC’s Charter is extended

The Royal Charter granted on 20 December 1889 for a period of 25 years, was extended for a further 10 years, expiring in 1924. The outbreak of war in 1914 affected the world, including Southern Rhodesia. Falling revenue, growing unemployment and difficult credit made it hard for [a community] of some 35,000 [white people] to support the war out of current revenue.[44]

The Company’s fight with the settlers continued. Revenues declined because the BSAC could not increase the customs duties because this pushed up living costs and the customs agreements pitted Southern Rhodesia against the Union, which was in a stronger position, and only small concessions were granted.

The Company proposed a loan to get by, but the Colonial Office refused, saying it would put the repayments beyond Southern Rhodesia’s present capacity.

The Privy Council rules that the land does not belong to the BSAC

The BSAC proposed a scheme to tax all undeveloped land holdings, including alienated areas, to collect more revenue and force the landholders to develop their land.

The Responsible Government Association, representing farmers, strenuously opposed and asked the Colonial Office to investigate the issue of the unalienated land ownership, Phimister argues that land was the BSAC’s most valuable asset and a major source of revenue.

In 1918 the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled against the Company; the Lippert Concession was worthless as a title deed,[45] but the company was granted a lien on the unalienated land until its claim for reimbursement of administration costs was settled.[46] Having lost this asset the BSAC saw no further point in subsidising administrative deficits and told its shareholders that, “since the land is not yours, capital for its further development must be sought elsewhere than from you.”[47]

The Privy Council ruling meant that any successor to the BSAC would not be able to use the unalienated land to its own profit until the British governments debt had been cleared.[48]

The Company retaliates the land decision by changing its financial policy

It immediately stopped its contributions to posts and telegraph costs and attempted to reduce expenditure on public works. Drummond Chaplin, the Southern Rhodesia’s administrator, addressing the Rhodesia Agriculture Union in 1919, stated that, “under the situation that has been created by the judgment of the Privy Council regarding land, it is practically impossible for me to get money for capital expenditure unless it is provided out of the country’s ordinary revenue of the year.”

In addition, the BSAC proposed adding income tax and an excess profit tax to Southern Rhodesia’s taxation system. Excess costs had been experienced in many departments that the company had paid for. It argued that it had experienced a budget deficit between 1914 and 1917 and needed new sources of revenue.

Newton, the company treasurer, believed there were sufficient grounds to introduce income tax saying, “There have been allegations that there is sufficient taxation in this country, but that position I challenge emphatically. I think we are possibly among the most lightly taxed populations. It is not a proposal to tax the poor and needy.” He argued receipts would be used to cover the increase in administrative cost because of the war and to provide for gratuities to married civil servants.

An income tax, special war tax and excess profits tax were imposed under the Provisions of the War Taxation and Excess Profits Duty for Southern Rhodesia in 1918 specifically to cover war expenditure.

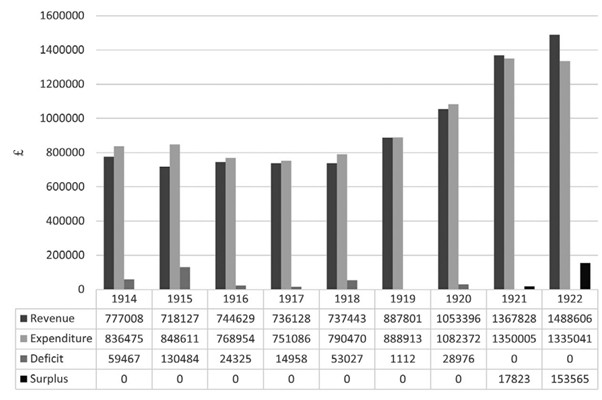

Revenue and expenditure of Southern Rhodesia 1914–1922. Calculated by H.E. Koke using statistics obtained from the Official Book of the Colony of Southern Rhodesia, no. 2, 1930.

Conflict continues to persist over administration costs

In 1920 a new Legislative Council was elected and 12 of the 13 members requested the Colonial Office to grant Responsible Government. A commission was appointed under Lord Buxton that gave a positive response.[49] Rhodesians ought to be able to choose between Responsible Government and the Union of South Africa.[50]

After 1920 when revenue collected exceeded administration costs the settlers were eager to take over Southern Rhodesia’s administration that was by then running a surplus. In the Legislative Council there were objections to income tax on constitutional grounds as long as the country’s citizens did not have full and independent financial responsibility for the country. (i.e. under Responsible Government)

These arguments and the commissions conclusions even drove the BSAC’s directors to say they wanted to give up the administration of the country as soon as possible.

The Colonial Office lays down conditions for Responsible Government (i.e. self-rule)

Those conditions were;

- Proven financial fitness

- Demonstrate the capacity to reduce the inequality between the European and African populations

Failure to meet these conditions meant Southern Rhodesia was not yet ready to govern itself. The BSAC backed the Rhodesia Union Association (RUA) arguing that it was a “laudable desire to wish for self-government, but no country could be governed by sentiment with financial resources necessary for administration lacking.”[51]

Coghlan disagreed with the RUA concluding that change from BSAC rule was both “desirable and inevitable” and noted that, “evidence of financial competency and fitness in other aspects was submitted, and readiness was affirmed [to tender] further testimony if called upon.”[52] He believed that with the country’s white population at 33,620 in 1921, they should be in control of the administration. He was supported by Crawford Douglas-Jones, the resident commissioner from 1918-23.

Southern Rhodesia votes against joining the Union of South Africa

It was in support of self-rule that the Responsible Government Association with Coghlan as its President argued against Southern Rhodesia becoming the fifth province of the Union saying the country could provide for its administration expenses. In the 1922 referendum campaign the RUA and RGA also disagreed on the taxation system and tax rates settlers would pay under Responsible Government.

The RUA said that a subsidy equal to that given to Natal and the Orange Free State would be enough for the country without having to increase existing taxation and would result in a budget surplus. The RUA believed the Union’s income tax would be favourable to Rhodesians; taxable income started at £300, and Rhodesia would be exempted for three years. It said taxation would be lower than under Responsible Government.

The RGA argued that the subsidy was gradually decreasing in the Union and administration costs were increasing and soon the extra taxation would be at least £250,000.

Note: Compiled by H.E. Koke with statistics obtained from The Rhodesia Herald, October 8, 1921.

In the campaign prior to the referendum General Smuts himself visited the country to persuade the settlers to join the Union of South Africa, but the prospect of higher future tax convinced the electorate and the RGA won the 17 October 1922 referendum paving the way for Responsible Government in 1923.[53]

The final settlement with the BSAC

Much bargaining then took place in London, the chartered company requesting to be paid in cash before it gave over its unalienated lands. The final agreement included both Southern and Northern Rhodesia. The British government agreed to pay £3.75 million in return for all the unalienated land, public works and buildings in both countries, whilst the chartered company kept its mineral and railway rights in both countries,

Subsequently, Southern Rhodesia was required to pay £2 million to the Colonial Office to reimburse the amount paid to the BSAC for past administration deficits, reducing the British government bill to £1.75 million. Gann makes the point that Southern Rhodesia was the only country in the British Empire which ever had to pay for the privilege of self-government.[54]

Southern Rhodesia becomes a British colony

As a colony the country had a Governor representing the Crown and who acted as the country’s constitutional and ceremonial head forming the link between Salisbury (present-day Harare) and London. He also presided over the Executive Council, composed of government ministers.

References

E.E. Burke. Buildings of Historic Interest No 6 ‘The Stables’ Salisbury. Rhodesiana Publication No 31, September 1974, P22-25

R. Cary. The Pioneer Corps. Galaxie Press, Salisbury, 1973

K. Chitoro. When Should We Expect a Reasonable Return on Our Investment Mr. Rhodes? The British South Africa Company Shareholders and the Profit Motive, 1890 to 1923.” Southern Journal for Contemporary History 46, no. 1 (2021): 137–158.

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter: The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974.

L.H. Gann. A History of Southern Rhodesia. Chatto and Windus, London 1965

A.S. Hickman. Men Who Made Rhodesia. BSAC Salisbury, 1960

R. Hodder-Williams. White Farmers in Rhodesia, 1890–1965: A History of the Marandellas District. Macmillan, London 1983.

H.E. Koke. Unfulfilled Promises and Desires: The British South Africa Company (BSAC), Settler Politics and the Development of Southern Rhodesia’s Fiscal System, 1890–1922. Enterprise & Society, Volume 25, Number 4, December 2024, pp. 1025-1048. Published by Cambridge University Press

P. Mason. The Birth of a Dilemma: The Conquest and Settlement of Rhodesia. Oxford University Press, 1958

I.R. Phimister. Rhodes, Rhodesia and the Rand. Journal of Southern African Studies Vol. 1, No. 1 (Oct 1974)

T. Ranger. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, 1896–1897: A Study in African Resistance. London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1967

J.P.R. Wallis. One Man’s Hand. Books of Rhodesia, Vol 22. Bulawayo 1972

Notes

[1] See the article Was Archibald Ross Colquhoun; first Administrator of Mashonaland 1890 – 92, a failure or was he actively undermined by Dr Jameson? under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[2] Crown and Charter, P261

[3] Gann, P104

[4] For more detail, see the article The British South Africa Company under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com. Charter Companies were not a new phenomenon; Britain’s East India Company (EIC) was formed in 1600, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. Contemporary charter companies of the BSAC established in Africa included the Royal Niger Company and Imperial British East African Company.

[5] See the article The Matabele Campaign of 1893 - the march on Bulawayo under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[6] Wikipedia

[7] Technically any territories gained by the BSAC should have been through treaties negotiated through the local rulers with the chartered company exercising the governing power on behalf of the Colonial Office

[8] Crown and Charter

[9] Lord Salisbury was Britain’s prime minister from 1895-1902

[10] Ibid, P108

[11] Buildings of Historic Interest No 6 ‘The Stables’ Salisbury: The Surveyor General wrote that at the date of his report, 22 August 1892, the Administrator was in his new brick building, which he shared with the Public Prosecutor, the Company's Accountant and the Standard Bank. This was in Jameson Avenue, across the road from "The Stables"; it was demolished in the 1940s

[12] Lord Knutsford was secretary of state for the colonies 1887-1892

[13] Crown and Charter, P107

[14] Ibid, P148

[15] See the article The Pioneer Column’s march from Macloutsie to Mashonaland under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[16] Crown and Charter, P257

[17] Rhodes, Rhodesia and the Rand, P88

[18] White Farmers in Rhodesia

[19] Buildings of Historic Interest No 6 ‘The Stables’ Salisbury. The Mining Commissioner’s and Survey Office, “constituted two L-shaped blocks in brick, with corrugated iron roofs; each block had three chimneys. By 1898 verandah’ s had been added and some trees planted. The detail of the verandah and of the windows can be seen in an illustration of the staff in 1907 (below) and many of these sash windows, each with six panes, remain

[20] There are several articles with references to the Adendorf trek on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[21] Crown and Charter, P262

[22] Men Who Made Rhodesia, P37

[23] Gann, P208

[24] Sir William Milton (1854-1930) Acting Administrator (1897-1898) 4th Administrator (1898-1901) 6th Administrator (1901-1914)

[25] Sir Ernest Lucas Guest (1882-1972) was a lawyer and prominent Southern Rhodesian politician well-known for his role in WWII as minister for air and for his support for Lake Kariba. For more information read the article The Rhodesia Air Training Group (RATG) 1940 – 1945 under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[26] Buildings of Historic Interest No 6 ‘The Stables’ Salisbury

[27] History of Southern Rhodesia, P215

[28] A supplemental Royal Charter was issued in 1915

[29] When should we expect

[30] History of Southern Rhodesia, P217

[31] Wikipedia – hut tax

[32] Revolt, P60

[33] Ibid, P74 - 77

[34] Gann P90 states Johnson was paid £87,000 and receive 40,000 morgen 84,678 acres and 20 gold claims for each of twelve friends nominated by him.

[35] The Pioneer Corps, P25

[36] Ibid, P29

[37] Ibid, P25

[38] Details are from Wikipedia: Administrative posts of the British South Africa Company in Southern Rhodesia

[39] NAZ, GEN/BR-British South Africa Company’s Policy Statement, not dated, 9.

[40] Raymer, Should Chartered Administration be Abolished?

[41] In 1920 the Lord Cave Commission reduced this to £4.4 million. (History of Southern Rhodesia, P244)

[42] Sir Charles Patrick John Coghlan, KCMG (24 June 1863 – 28 August 1927) was Southern Rhodesia’s first prime minister (29 April 1924 – 28 August 1927) after it became a British self-governing colony. He was honoured for his services with his burial near C.J. Rhodes and L.S. Jameson at World’s View in the Matobo Hills.

[43] One Man’s Hand, Intro

[44] Ibid, intro

[45] See the article Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[46] One Man’s Hand, Intro

[47] Phimister, Economic and Social History, 99.

[48] History of Southern Rhodesia, P233

[49] One Man’s Hand, Intro

[50] Smuts terms were very generous. Rhodesia would have ten and ultimately seventeen members in the Union parliament with four seats in the Senate. The Union would take over the railways, upgrade Beira, spend no less than 0.5 million over ten years on development and but the BSAC’s land and mineral rights.

[51] RUA Manifesto: The Case Against Responsible Government, 1922.

[52] One Man’s Hand, P168.

[53] 8,774 votes for Coghlan and Responsible Government; 5,989 for Union (History of Southern Rhodesia, P246)

[54] A History of Southern Rhodesia, P248